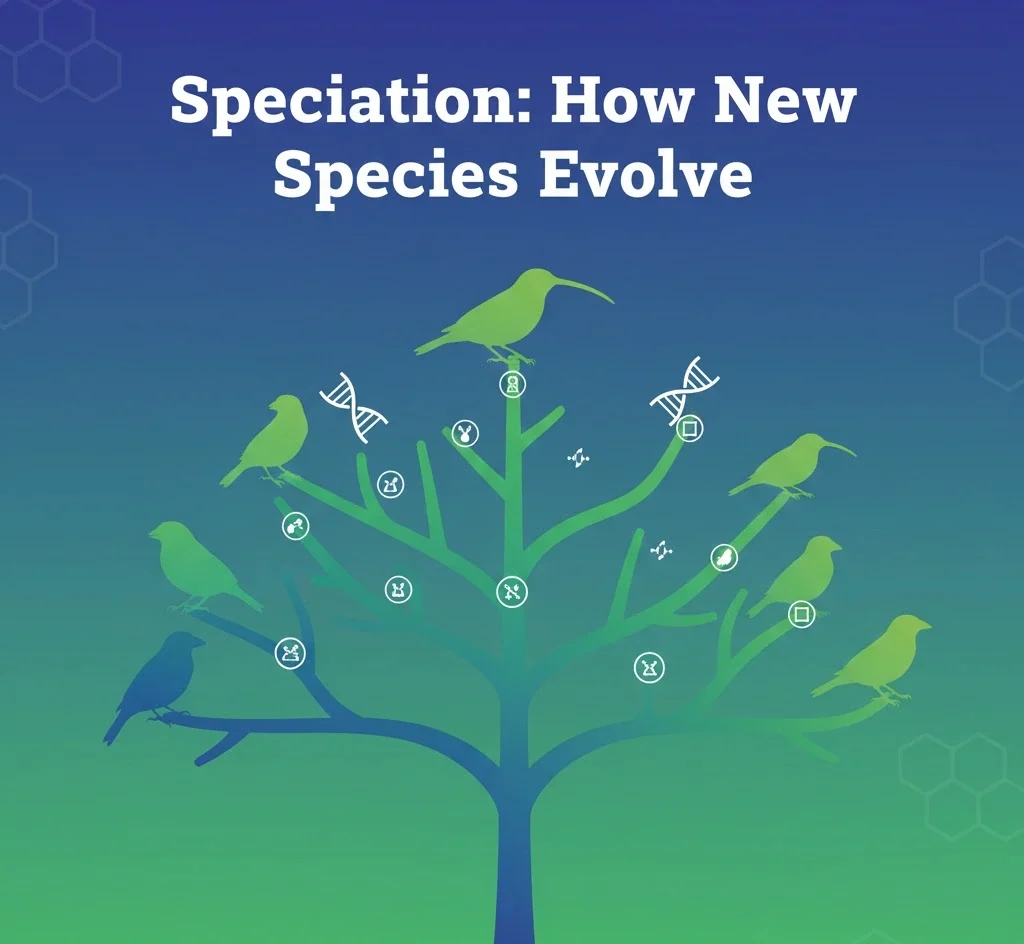

Ever wonder how we ended up with over 10 million different species on Earth? The answer lies in a remarkable process called speciation—and it’s happening right now, all around us.

The phenomenon of life being so drastically different yet coming from the same ancestor has always been a great source of fascination to me. Speciation, on the other hand, is the evolutionary process that splits one population into several distinct species, each one perfectly matched to their environment. The change in beak shapes of Darwin’s finches in the Galápagos Islands or the dazzling variety of cichlid fish in African lakes are some of the examples that illustrate the distinctiveness of this evolutionary process to the very core of our natural world.

Grasping the concept of speciation is not merely a matter of having the knowledge but also comes with the advantages of being able to save endangered species, foretell the reaction of organisms to the changing climate, and admire the vast array of life. I am now going to take you through the tour of how this amazing process works.

What Exactly Is Speciation?

Speciation refers to the evolution of populations into distinct species through natural selection. It can be thought of as the mechanism through which nature splits the tree of life—one lineage gives rise to two or more new paths that are unable to interbreed.

The idea was already present in Charles Darwin’s revolutionary studies in 1859, though the term was first introduced by the biologist Orator F. Cook in 1906. What is a bit of a paradox about speciation is that it represents both the unity and diversity of life at the same time. All living beings share common ancestors, but at the same time, they have evolved into millions of different forms.

The very heart of the matter is that speciation occurs when the genetic alterations build up to such an extent that the populations do not mate anymore. In other words, fertile offspring cannot be produced when such populations are interbred—no matter how hard they try. The reproductive barrier is the main criterion that separates species in the biological species concept.

The Genetic Foundation of Speciation

At the very start of the process of speciation, there are the molecular level and the mutations in the gene. These are the changes in DNA that are minute indeed, and they can be of different types such as point mutations, insertions, deletions, or even gene duplications; still, all of them have opened the door to the variation of populations. The majority of mutations are either neutral or slightly harmful, yet now and then one mutation gives the individual a competitive edge.

Over a course of generations regarded as decades, the genetic differences between the populations get a chance to accumulate and the populations start to change. Natural selection and random genetic drift take the alleles’ frequency in different directions. Genetic drift in small populations can be particularly powerful and lead to significant divergence quite quickly. This phenomenon is known as the founder effect whereby when a few individuals from a population with a certain genetic makeup move to a new place and start a new population, then the genetic characteristics of the old population will be passed on to the new one.

It is really interesting that epigenetics, which is the process of changing the gene expression without changing the DNA, can also be a force in speciation. Different environmental factors such as temperature, diet, or stress can either activate or silence genes resulting in inheritable differences that eventually lead to the isolation of the populations.

Reproductive Isolation: The Final Frontier

The defining moment of speciation is reproductive isolation. This is when populations become incapable of producing fertile offspring, sealing their genetic separation. These barriers fall into two categories that scientists call prezygotic and postzygotic barriers.

Prezygotic barriers prevent mating or fertilization from happening in the first place. You’ll see this with species that breed in different seasons (temporal isolation), use incompatible mating rituals (behavioral isolation), or simply can’t physically mate due to anatomical differences (mechanical isolation). Some species even reject each other’s gametes at the cellular level.

Postzygotic barriers kick in after fertilization. The hybrid offspring might die during development, be born sterile like mules (offspring of horses and donkeys), or produce weak, unfit descendants. These barriers ensure that even if two species occasionally interbreed, their genes don’t blend back together.

Four Paths to New Species

Geographic separation drives most speciation events through allopatric speciation. When mountains rise, rivers change course, or islands form, populations get physically divided. Arizona’s Grand Canyon perfectly illustrates this—squirrels on the north and south rims evolved into separate species after the canyon split their ancestral population thousands of years ago.

Sympatric speciation happens without any geographic barrier, which honestly seems almost impossible at first glance. How do populations living in the same place diverge? It turns out behavioral changes or ecological preferences can do the trick. Apple maggot flies originally laid eggs only in hawthorn fruits, but some shifted to apples when colonists brought apple trees to North America. Those populations now breed at different times and are evolving into distinct species.

Parapatric speciation occurs when populations live side-by-side but adapt to different microhabitats. Grass growing in mine-contaminated soil, for example, develops metal tolerance and stops breeding with nearby uncontaminated populations. The two groups are neighbors but ecologically separated.

Peripatric speciation involves small groups breaking off from larger populations. Because these founder populations start with limited genetic diversity, they can evolve rapidly through genetic drift and strong selection pressures. Many island species evolved this way.

Natural Selection and Environmental Pressures

Natural selection acts as the sculptor of speciation, favoring traits that improve survival and reproduction in specific environments. When populations face different ecological challenges, they adapt in different directions.

The classic example is the peppered moth during England’s Industrial Revolution. As pollution darkened tree bark, dark-colored moths suddenly had better camouflage than light ones. Within decades, the population shifted dramatically. More dramatically, brown bears that migrated to Arctic environments faced intense selection for white fur, fat storage, and cold adaptation—eventually becoming polar bears, a completely distinct species.

These adaptations accumulate gradually. A population doesn’t wake up one day as a new species. Instead, small advantages compound over thousands or millions of years until the genetic differences become insurmountable.

Real-World Examples That Bring It All Together

Darwin’s finches are the most classic example of speciation in progress, remaining as such in the textbooks. They were birds that first migrated from the mainland of South America to the Galápagos Islands, then they differentiated into 14 species. The different birds got different beaks according to their foods—some eat seeds, which they crack, some get water from the cactus flowers, while some even use tools to get insects.

The Rift Valley lakes of East Africa were gifted with the cichlid fishes as an exemplification of rapid speciation. Ancestral populations turned into over 800 described species in 10,000 to 15,000 years, as the species worked the process of evolution by natural selection. In Lake Victoria alone, there are hundreds of differentiated cichlids, which are different in coloration, feeding methods, and behaviors. It is thought that sexual selection in combination with ecological opportunity were the primary factors behind this impressive radiation of species.

The three-spined stickleback is a good example again. Marine sticklebacks were the first fish to reach freshwater lakes and streams after the last ice age. Structural differences between populations now exceed those between different fish genera, which means that fin shapes, bony plates, jaw structures, and colors have changed in so short a time as 10,000 generations, in order to adapt to their new environments.

How Humans Influence Speciation

Urbanization is now one of the dominant forces in the process of natural selection. The cities have their own exceptional conditions which allow for quick adaptability to take place. For instance, the city-dwelling pigeons have developed not only different habits but also diverse gut microbiomes in comparison to their country counterparts.

Humans have been knowingly causing speciation in domesticated plants and animals through selective breeding for thousands of years. Dogs of today are direct descendants of wolves due to human selection, and many dog breeds are so genetically different that they would qualify as separate species if they were living in the wild.

Habitat destruction and climate change are even worse than the above situation because they are literally pushing the species into new areas of contact thus creating the hybrid zones where interbreeding of previously separated species is taking place. Sometimes this results in the creation of novel hybrid species but more often it endangers rare species due to the genetic swamping by their more common relatives.

Why Speciation Matters Today

Understanding how speciation occurs and what maintains the isolation of species, we can protect biodiversity spots better and build up wildlife corridors that would allow for the mixing of genes. Conservation genomics or the study of evolutionary potential of endangered populations helps us in pinpointing the populations that are most crucial to conserving.

Speciation research also has a bearing on human health. The bacteria and viruses are constantly dividing and leading to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains and diseases. The knowledge of the process that these microorganisms evolve reproductive isolation can result in the development of better treatment methods.

Principles of speciation are the main factors that direct breeding programs in agriculture. The production of drought, pest or climate change tolerant varieties rests on the same evolutionary mechanisms creating new species in nature. In this age of changing world conditions, relying on speciation processes for food security becomes an absolute necessity.

The Ongoing Debate and Future Research

Controversial topics have been under discussion by scientists about the speciation mechanisms’ relative importance and are not likely to be settled in the near future, even after more than one and a half centuries of research, starting with Darwin. The first question to be addressed is how often it takes place that species emerge without the barrier of geographical separation? The second one is, what is the role of genetic drift compared to that of natural selection? These are just some of the questions that lead researchers to genomic sequencing with the help of the most modern technology.

You May Like: https://buzzovia.com/what-is-potnovzascut/

The cutting-edge technologies now allow speciation to be observed as it happens through the tracing of genetic changes in real-time. The researchers are able to spot certain genes that are responsible for reproductive isolation and also to show precisely how the genomes of different species are changed during the course of that species formation. Moreover, the use of machine learning has made it possible to predict the evolution of the populations under different climate scenarios.

The idea that horizontal gene transfer—which is a process of gene swapping among organisms other than through mating—has a huge impact on microbial speciation has thus overturned the classical views on the matter. However, this situation complicates the definition of a species among bacteria and archaea; nevertheless, it also leads to new areas of investigation which could have ramifications through the entire tree of life.

The ability to comprehend speciation brings us closer to nature’s deepest patterns on Earth. Every species, including humans, can be seen as the end-point of infinitesimal speciation events that go back to the very beginning of life on planet Earth about 4 billion years ago. We are all part of an unending evolutionary saga, which by the same factors that brought about the incredible diversity around us, continuously reshapes our world.

The generation of new species is not simply a historical fact—it is a process that is currently going on, impacted by both nature’s forces and human activities. With nature undergoing rapid changes, a good understanding of speciation not only helps us preserve the biodiversity which is vital for our planet but also reminds us that adaptation and change are intrinsic to life itself.